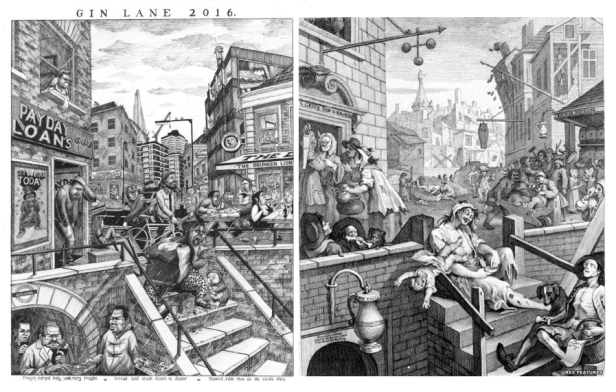

Last week, a re-imagining of Hogarth’s Gin Lane was unveiled. Commissioned by the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) and Billed as Gin Lane for the 21st century, the update replaced gin with a plethora of more modern ‘evils’; particularly obesity and poor mental health in its various forms. Although some welcomed the image as an arresting vision of the challenges facing public health in Britain today, I found the picture troubling for reasons I discuss below.

Last week, a re-imagining of Hogarth’s Gin Lane was unveiled. Commissioned by the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) and Billed as Gin Lane for the 21st century, the update replaced gin with a plethora of more modern ‘evils’; particularly obesity and poor mental health in its various forms. Although some welcomed the image as an arresting vision of the challenges facing public health in Britain today, I found the picture troubling for reasons I discuss below.

Top of my list is the deliberately grotesque caricature which takes centre-stage and replaces the famous image of the breast-feeding mother swigging gin while her baby tumbles down a staircase. The modern pastiche gives us an obese mother, mouth wide open, burger in one hand and phone in the other while her baby shares her chips. The baby is in a onesie with ears while the mother is dressed in leopard-print leggings and a top so small that only anatomically-dubious drawing protects her decency. In combination, these stylistic choices seem designed to define the woman as, for want of a better word, a ‘chav’ and it is hard to escape the sense that we are intended to both judge and blame her for being in a disgusting state and, worse, for inflicting the same destiny on her young child.

These unsympathetic caricatures consistently seem to target the working class. There is the overweight wine-drinker, crammed into a too tight black dress with cleavage on show and fag in hand. In the background, we see a man exiting a chicken shop with his belly showing between his top and bottoms and the overall impression is this is a deprived part of town. You may be thinking I am just assuming these are working class people and that middle class people dress like this too. Perhaps this is true, but look at the more sympathetic depictions of those who are unambiguously in white-collar roles (identifiable by their wearing of a white collar). At the top of the image we have a slim man committing suicide. Beneath the lamp-post, a somewhat overweight woman in a suit is sipping from a drink and looking generally unremarkable. In the bottom-left corner, business-people of varying shapes accept newspapers proclaiming an obesity crisis. In each case, no attempt is made to use these professionals’ bodies to provoke us. It seems to be only the working class who have shocking bodies meriting condemnation.

Another concern, is who isn’t in the new Gin Lane. We see the chicken shop, the bookies, the payday lender and the pub. Yet, 21st century public health recognises that there are often corporations behind these businesses and that the actions of individuals within those corporations have a profound impact on the well-being of our society. None of these individuals are pictured. Where is the villainous multi-national CEO or his smooth-talking lobbyist who are surely both, for the RSPH, more deserving of an unsympathetic caricature than a woman in colourful leggings?

Finally, I worry about the overall impression left by this vision of contemporary Britain. Why does the image of an underclass stewing in their own juice hover in my mind rather than the sense of a system needing intervention at multiple levels? Why does the Shard in the background only reinforce a sense of a world apart where the poor eat, drink, bet, smoke and borrow themselves into despair and then do it all again as the next generation comes of age? And no, adding a hipster touring the wreckage like a latterday character from Common People doesn’t make this feeling go away; not least because a hoodie (hello, 2004!) appears to be about to kick the crap out of him.

Finally, I worry about the overall impression left by this vision of contemporary Britain. Why does the image of an underclass stewing in their own juice hover in my mind rather than the sense of a system needing intervention at multiple levels? Why does the Shard in the background only reinforce a sense of a world apart where the poor eat, drink, bet, smoke and borrow themselves into despair and then do it all again as the next generation comes of age? And no, adding a hipster touring the wreckage like a latterday character from Common People doesn’t make this feeling go away; not least because a hoodie (hello, 2004!) appears to be about to kick the crap out of him.

There are positives to the image. As a PR stunt which gets people to think about contemporary threats to our health and how these have changed since Hogarth’s time, this update of Gin Lane is a modest success. But, as social commentary, it is too often crude and tactless and, as satire, it takes cheap shots at the weak without pulling the powerful into the dirt. It brings us face-to-face with the public’s health in the 21st century but blames individual morality and Broken Britain rather than illuminating the complex, systemic and power-infused challenges which should be with the RSPH’s sights. Maybe a re-imagining of Gin Lane could never live up to modern understandings of public health without losing the connection to its source. But perhaps that’s the point. Perhaps like Hogarth’s original, the 21st century Gin Lane is as interesting for what it says about our contemporary attitudes and how little they have changed as for what it says about the problem it depicts.

No beer street then?

LikeLike